The first sound we hear on Bat out of Hell II is exactly what one would expect: a motorcycle revving its engine. I presume that it’s a guitar just with a better version of the motorcycle effect than what Rundgren had back in 1977, though it could easily be a synthesizer instead. When Roy Bittan’s hyperspeed piano riff begins and Tim Pierce and Eddie Martinez’s guitars start punctuating it, it’s so clear that we are in Bat out of Hell territory that, if it weren’t so great, it would be easy to worry that we’re again getting a copycat version of the first album.

But then everything quiets down to a mix of piano, soft backing vocals, and bass for Meat Loaf’s surprisingly restrained vocal opening. Where “Bat out of Hell” was a breakneck rocker that didn’t let up until well into the song, “I’d Do Anything for Love (But I Won’t Do That)” is actually a ballad with a hard rock introduction. Synthesizers replicate strings and gongs to help build the drama and guitars slowly get introduced until another heavier instrumental section explodes with drums and booming power chords. Steinman repeats this pattern of heavier and softer sections through the first guitar solo. Every time, the guitars and drums stay a bit more in tact the next time it softens up and the backing vocals stay a little more present the next time it goes more rock, culminating in a booming second chorus that makes any previous “wall of sound” seem more like an underpinning by comparison.

But then, the song goes back to as soft an arrangement as it has ever used for a short verse before a completely unexpected duet call-and-response bridge between Meat Loaf and Lorraine Crosby with a different melody from the rest of the song. It’s close to the verse melody and it sounds like it all belongs together, but the call-and-response is close to a traditional bridge. As the two trade lines, she is first backed by some bluesy guitar leads and he is backed by backing vocal “ahh”s and power chords only for those to merge as they go. But then she changes her tone completely and everything else largely fades away to leave a bit more call-and-response over a piano and then Meat Loaf’s final plaintive repeat of the title as it fades way.

Steinman’s epic ballads have been built around a dramatic rise in volume, going from small piano-based arrangements to bombastic, Wagnerian symphonies. But none before scaled quite these heights. Even “Making Love out of Nothing at All” seems restrained compared to the loudest parts of this song. And that all of this bombast is followed by a memorable duet that both musically and lyrically shows the two singers’ attempt and failure to find common ground is simply a beautiful bit of melodrama.

To address the elephant in the room about the lyrics, the titular “that” is actually explained in the song, but not in the way most people are expecting. It’s not a single thing but rather a different thing each verse. Taking the song from the start, he says, “And I would do anything for love/I’d run right into hell and back/And I would do anything for love/I’d never lie to you and that’s a fact.” He would run right into hell and back and would never lie to her. Then he says, “But I’ll never forget the way you feel right now–oh no, no way.” The line even starts with “but,” as he proclaims that the thing he won’t do is forget how she feels right now: “I would do anything for love/But I won’t do that.”

The same grammatical structure continues after that: “I would do anything for love/And I’ll be there ’til the final act/I would do anything for love/And there will never be no turning back/But I’ll never forgive myself if we don’t go all the way–tonight.” However, in spite of his use of the word “love,” it’s pretty clear that what he’s really pleading for is sex. Fundamentally, every one of his verses breaks down to, “Yeah, I will love you forever/But we need to have sex right now.”

So when she joins in, she starts asking him if he will do things similar to what he’s already vowed: “Will you raise me up? Will you help me down?/ Will you get me right out of this godforsaken town?/Will you make it all a little less cold?” He affirms: “I can do that! I can do that!” She continues upping the stakes until, “Will you cater to every fantasy I got?/Will you hose me down with holy water if I get to hot?/Will you take me places I’ve never known?”

When he screams “I can do that!” one final time, she turns the tables on him by saying, “After a while you’ll forget everything/It was a brief interlude and a midsummer night’s fling/And you’ll see that it’s time to move on.” He quietly, defensively responds, “I won’t do that.” She says, “I know the territory; I’ve been around/It’ll all turn to dust, and we’ll all fall down/After a while, you’ll be screwin’ around.” He again proclaims that he won’t do that, then repeats the title phrase as we fade out.

It’s a song about differing expectations and the resulting strain on a relationship, or in this case even a potential relationship. That’s a Steinman theme through and through, and doing it through a call-and-response duet where the Boy is begging for sex has to bring “Paradise by the Dashboard Light” to mind. But where the older song eventually had them agree to both sex and the strings attached, only to regret it thereafter, this song sees the Girl, clearly the more street-smart of the two, stand up and say, “I know where you’re really going, and I’m not letting this happen.” Frankly, while I think he would have argued with me saying this, I think it’s a very feminist statement–she can absolutely turn Meat Loaf down, because she can absolutely see through his artless claims of “love.” There’s even something hopeful about the fact that this time it isn’t a song of regret, at least not for both parties. Since his final words are a plaintive cry of of “I would do anything for love/But I won’t do that” on top of just a piano, I think it’s fair to say that there is regret and longing on the part of Meat Loaf, but there is no suggestion that a crippling, lifelong commitment was born of this encounter the way there was in “Paradise by the Dashboard Light.” Society has progressed, at least somewhat, and allowed these two to have a very different encounter than the Boy and Girl in 1977, even if they entered with many of the same thoughts.

For years, I was enthralled with the introduction to this song and loved the chorus but was kind of impatient with the rest. But as I listened to it more, especially after I heard “Paradise by the Dashboard Light,” I kept finding more to appreciate about it. Steinman’s songs appeal to me for a number of reasons, but high on the list are that he talks about complicated emotions and relationship situations instead of the typical musical tropes of teenaged love songs (even when his songs are about teenagers) and that he actually rejects traditional gender roles by presenting them and the issues with them so clearly. The former is clear in “I’d Do Anything for Love” anyway, but the latter is there in large part because of the contrast with its predecessor, which is an absolutely brilliant use of the fact that this is a deliberate sequel.

It’s a brilliant song that deserves every bit of its worldwide hit status, even if it did spawn an annoying pre-internet meme because the lyrics were too complicated for radio listeners. I even think that the 12-minute (!) album version actually works infinitely better and feels shorter than the radio edit that kind of throws the listener wildly around instead of building organically.

And even beyond how good the song is, the fact that the opening song with the motorcycle and long instrumental opening actually turns out to be the ’90s version of “Paradise by the Dashboard Light” makes it clear that there is some real thoughtfulness going into this album in the way that was missing on Dead Ringer and Bad for Good. It knows it’s a sequel, but it used that to make itself more meaningful instead of either just replicating what worked before or trying to force a song to fit where it didn’t belong, and that evinces a confidence that neither Steinman nor Meat Loaf seemed to have back in 1981.

Notes

- This song is chock-full of absolutely stunning lyrics. And I think it’s intentional that the Girl gets a ton of them even though she’s not there for that much of the song.

- A personal story: I remember ripping this album to my computer (This is pre-iPod, back in the days when I used CompactFlash cards for my RCA Lyra. I had tons of music on the computer and got roughly two albums’ worth to listen to during a day.) I ripped this entire album and gave every song on it five stars except this one, which I gave four stars. It’s now one of my favorites on the album.

- I long resisted saying anything like this, but I do feel like this is the quintessential Steinman song–it really has everything he was regularly trying to do. If someone wanted an introduction to his work, this is probably the best place to begin.

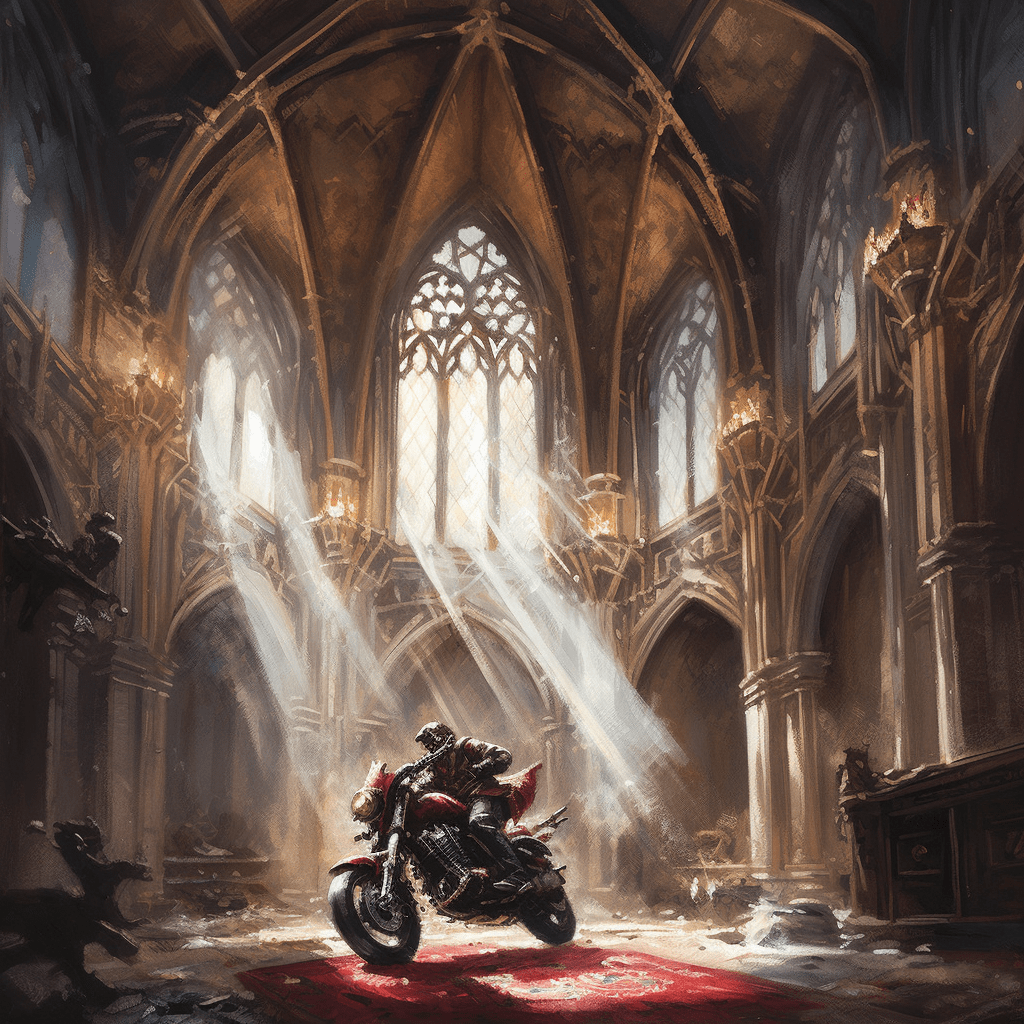

- This is getting a bit afield, but I so wanted to get a Midjourney piece for this song that looked like a biker crashing through a window into a cathedral where a woman was sitting at a piano, thoroughly unimpressed. That was too complicated to get out of it (at least for me), but also surprisingly impossible to get because of the AI’s content moderation–apparently a biker crashing through a window is too violent. It was frustrating.

Leave a comment